Permaculture design is a holistic design process where we work with the natural patterns and expressions of life processes to create spaces which simultaneously meet our needs as human beings while maintaining harmony with the web of life. The result are healthy gardens, buildings, and ecosystems. Originally born out of a discussion between David Holmgren and Bill Mollison back in the 70s concerning why the fields of Landscape Architecture, Ecology and Agriculture are separate rather than integrated with each other. Permaculture is the result of bringing those fields back together.

We start with the Human Element upon the land. The human being has the potential to be the most creative or destructive of the land’s inhabitants. The mind and heart of the human element, their vision for the land is a critical beginning point in this process. Permaculture design principles do not see the human as separate and apart from “Nature” but a vital and powerful component of Nature. The most exquisite permaculture design will fail, if the human beings who will implement, caretake and evolve it are excluded from the design process and if it fails to embrace their vision for their land. In our process here of evolving a multigenerational land, the human element must include mapping out future scenarios for the children, grandchildren and future generations who will inherit the evolution of the permaculture design.

WE BEGIN BY ASSESSING, RESEARCHING, and MAPPING RAW AND LIVING ELEMENTS

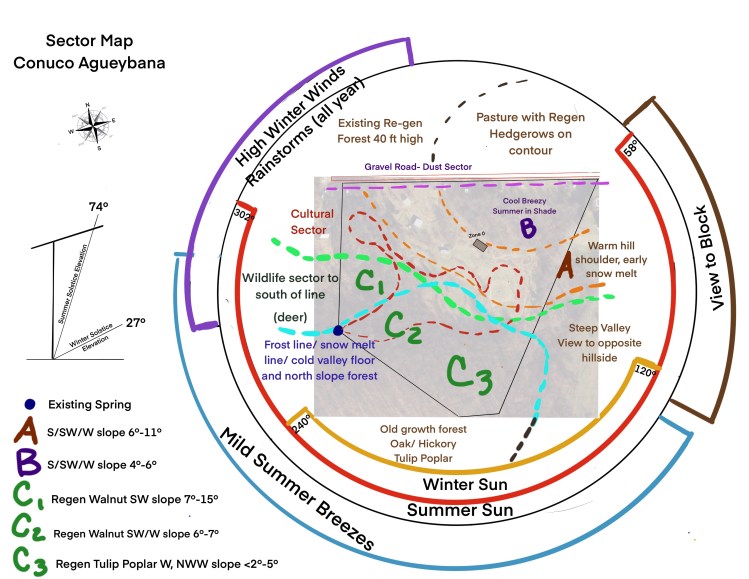

In Permaculture design processes, we assess the primary elements that will effect our land. First we have the landform itself, its altitude, slopes (aspect and steepness) as well as location and climate. Then we look at raw elements such as, the Sun (angles throughout the year), Water Cycle and Flow across the land, Winds (hot/ dry, cold, wet), Frost Lines and Sunbelts, and Storm directions.

We are in the Chesapeake Bay bioregion on the east coast of a large continent. This means that we have an abundance of rain. We are inland approximately 100 miles from the Atlantic Ocean and 40 miles from the bay, and the Blue Mountains are approximately 100 miles to our west. The land is on a ridge from where we can see the Catochtin Mountains. The land can certainly be classified a hill country.

Raw elements

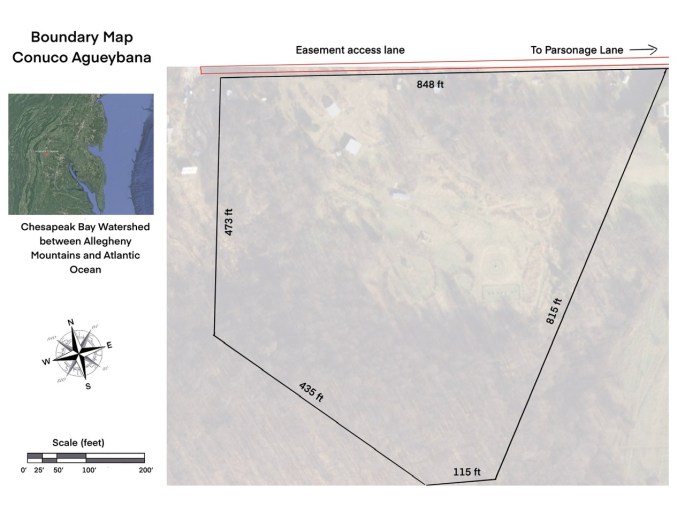

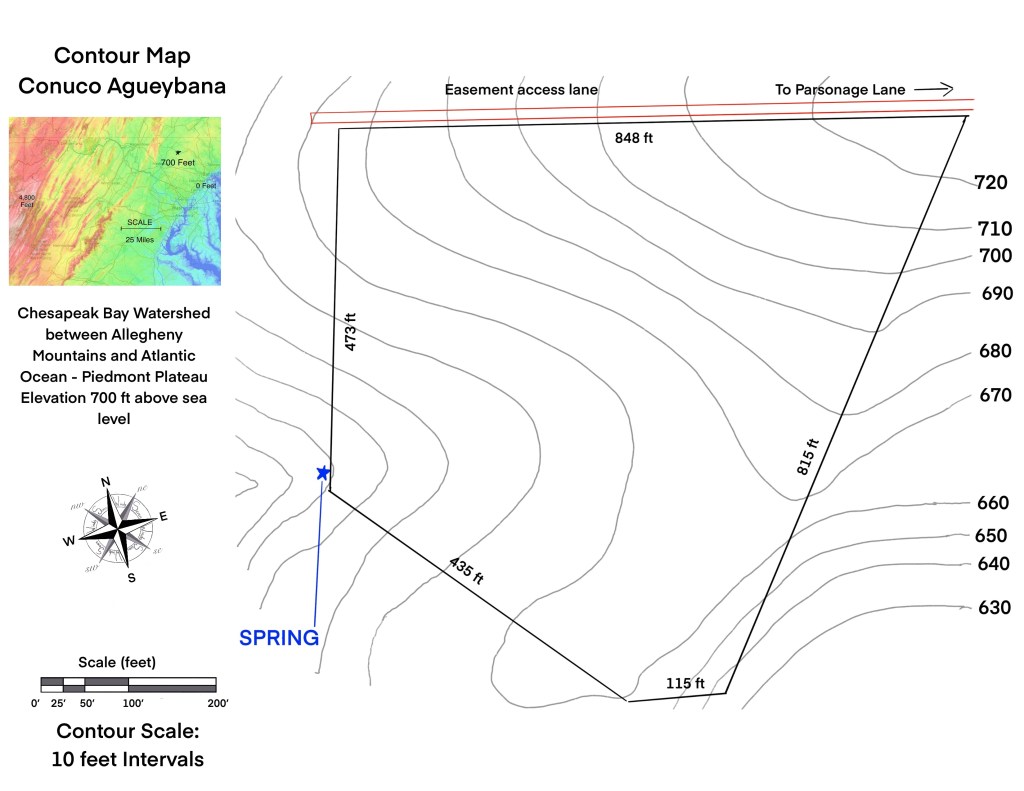

Raw elements are those forces and materials which give each place a unique expression. The way the Sun moves through the season, the way the Water Cycle moves (storms, hurricanes, glaciers), Winds, Minerals of the Bedrock below the soil, Volcanoes, Climate, these are the forces which have shaped the land we stand on. It benefits us to begin a process of understanding these raw elements. In this process we map out our land and begin the research and observation process. Our beginning point is a boundary map which also gives us an idea of the larger region in which the land is located and a contour map which gives us measurements of slope and aspect.

At this point research is generated concerning important considerations such as:

- Longitude and Latitude

- Winter and Summer Sun Angles

- Distance from Large bodies of Water, Coasts and Mountain Ranges

- Climate Classification (Koppen and USDA)

- Rainfall- averages, extreme events, drought periods, flooding

- Temperature averages and extremes

- Wind direction- especially extremely cold, wet or dry winds

- Storms- seasons and directions

- Slopes are calculated based on contour map

- Slope aspect is noted

- Water flow over the land

- Seasonal and permanent streams, rivers, ponds, or wetlands

- Mineral content of the soil, soil pH, soil contaminants

Here major elements include hot and humid summers, consistent precipitation, cold winters, cold northwestern winds and dramatic seasonal changes. All these are accounted for in the design process. Our Koppen Climate Classification is Cfa (Mild temperate, fully humid, hot summer) and our USDA zone is 6b. Rainfall is consistent throughout the year, with an average rainfall of 42.5” (ranging from driest year 21.5” to wettest year 62.6”). We can have up to 2-3” of rain over a couple days at times. We have thunderstorms with high winds, and occasional mild tornadoes. Snow and ice can be major factors in winter. Our prevailing wind is Northwest, especially for cold winter winds and storms. Winds shift to milder Southwest winds in the summer. Large snows from the Northeast can occur in winter (Nor’easters). Temperatures typically range from true frozen conditions in winter to hot humid summers. (Average winter low is 24.5F and average summer high is 86.2F) but we can easily see below zero temperatures in winter and 100F or higher in summer.

Slope and aspect varies widely throughout the land with slopes in all directions and areas of almost flat land to steep slopes. Our altitude ranges from 720 feet above sea level to about 500. We have numerous springs, and streams that can run almost dry during drought. Flooding is not an issue.

Living elements

An assessment of the existing major living elements is undertaken. These include trees, shrubs, perennials, pastures, regenerating woodland, endangered species, existing wildlife trails, or presence, domestic animals, and domesticated gardens, orchards or crops. Very often valuable living elements present may need protection, or enhanced habitat.

The story of the land (historical use)

Prior to jumping into the material details of the land, gathering stories of its past use can be of great importance. Agriculture (including deforestation) as practiced in contemporary times, has the effect of degrading the soil, and destroying the healthy hydrology of the land. Large quantities of pesticides, herbicides and chemical fertilizers have been sprayed on most farmland resulting in contaminated, compacted dirt which needs regenerating into soil. Other areas may be contaminated from various industry waste streams. As permaculture designers, we may be beginning with contaminated ”dirt” rather than healthy living soil.

The land here has been an orchard for the last 150 years, until more recently when it was used primarily as pasture and hay. As an orchard would have been heavily sprayed, and the hay fields were sprayed with herbicide. There is little organic matter in the soil, which is high clay and rock, and somewhat acidic (as is typical here). The pastured animals were, to our knowledge, sheep and cows. Once the land came into our hands, we created gardens, orchards and pastures, as well as planted many trees. We obviously do not use any sprays, so this land has been ”organic” since then.

Assessing living elements

The living elements are plant and animal, bacteria and fungi upon and within the land. While we cannot know all the living elements, we can assess what we do recognize or what is in an abundance upon the land.

Plants

We know peaches, apples, pears and cherries were here and still have a number of the apples, cherries and peaches (or their descendants). These types of old orchards can have some very good, regionally adapted varieties.

Much of the land is naturally regenerated forest, some very scrubby, some high quality. Some of the trees that are naturally regenerating in abandoned pasture are: Robinia psuedoacacia (Black Locust), Liriodendron tulipfera (Tulip poplar), Juglans nigra (Black walnut), Prunus serotina (Black Cherry), Sassafras albidum (Sassafras), Sumacs, Oaks, Juniper virginiana (Red cedar), Morus nigra (Black Mulberry), Plantus occidentalis (Sycamore).

Sambuccus nigra (Black Elder), Black Raspberry, Wineberry, Black berry, Wild roses, climbing roses, as well as countless herbaceous species can be found in abundance.

Our dominant pasture grass is a warm season grass- Purple top tridens. As typical of warm season grasses it is clump forming and allows many wild flowers and “weeds” to grow in the spaces between the clumps.

It is essential to know of any plants which may be problematic to us or our garden plants. In our area poison ivy is a vine that causes an itchy rash for most people, and black walnut is a tree that suppresses the growth of some other plants, including many typical garden vegetables.

Animals

The wild animals by far out number any domesticated animals. While we cannot assess all the species of animals present, especially insect and soil species, we need to have an idea of migratory patterns, wildlife trails, and those wild animals which may be in conflict with some of our garden or domestic animal arrangements. We need to know who are the major herbivores and who are the major predators. Are their any animals who are poisonous to us?

In our area white tale deer are the major wild herbivore, with rabbits and groundhogs as lesser threats to our gardens. Young trees need protection from the deer, and their favored crops such as corn benefit from protection or location very close to the house. The deer may be more bold in their eating patterns in winter, especially during snows. Our major predators are foxes and hawks, which will readily hunt chickens and pigeons, especially when they have young. Understanding the seasonal cycle of major herbivores and predators is important, as protection may not be necessary year round.

Bird fruit predators will feast on blueberries and other berries, which may require netting, however our approach here is to plant significantly more than we expect to harvest to accommodate our bird community members.

Insect plant predators generally have either birds, bats or other insects which will predate on them. Diverse planting with plenty of highly aromatic herbs greatly reduces insect pressure on crops, combined with rotating crops. In the first few years of vegetable gardening here, our insect pressure was very high, however in recent years it has been much lower due to the recovery of the biodiversity of the ecology here.

Bacteria and fungi

Pastures are generally bacteria dominant, forest fungi dominant. During the process of forest regeneration the soil balance shifts from bacteria dominant to fungi dominant. However both bacteria and fungi are present in both spaces. The various biocides used in conventional land practices are deadly to the healthy bacterial and fungal ecosystem of the soil. It is for this reason that permaculture design focuses so heavily on restoring healthy soils, building organic matter, and constantly feeding and protecting the soil life through mulching, cover crops, chop and drop, and using sacrificial trees and plants simply to build soil and feed its life. The soil organisms eat just as our domesticated animals do, and we design to feed them, just as we do ourselves.

At this point the sector map can be created. It shows the directionality of major raw elements as well as sectors of living elements. At this point we are moving deeper into understanding major niches within the land. Where is it very wet and shady, dry and windy, sunny, cool? Where are old growth trees, young haphazardly regenerating trees, old abandoned pastures? Is their an ’ugly view’ we want to block, smell, dust or noise to block. Where is the winter wind coming in, how about welcome summer breezes, or dangerous hot dry winds (in fire prone areas)?

circling back around to the human’s vision and needs

At this point we have gained important understandings of the living and raw elements at play on the land. We circle back to the human element in this web of life. The human has the most complex array of needs. Shelter, diverse nourishment, clean water, may form the foundation of those needs and must be present inside of the design process, however many heartfelt desires and visions for the land guide the design process in unique ways.

The vision of an intergenerational land acknowledges that there is a pressing need for a reestablishment of bioregion specific knowledge bases. The depth of region specific knowledge requires intergenerational transmission and requires that each generation build upon the wisdom of the previous generations. Since one of the principles of our endeavors here is to accumulate, preserve and share this generational knowledge for our specific area, there is a requirement that we design to find, enhance and create a diversity of niches in which to trial guilds of plants and animals. These trials will build upon themselves, becoming every more sophisticated and evolved. This is a completely different approach than we would take if we were designing for a production system with ease of harvest, potential inclusion of mechanization and access for large equipment. The latter case would need simpler guilds and larger niches. Another way to see this would be to think of the difference between a highly evolved garden, with multiple layers of plants and animals, compared to a field of apple trees with comfrey, clover and some aromatic herbs. Both are wonderful and both have their place, depending on the vision of the humans who will caretake the spaces.

Water

Water is the essential element which will determine the potential for our land. It is also the element that is becoming more erratic as the climate changes. Storm rains are getting heavier, droughts becoming longer and fire pressure mounting. In addition, deforestation propels semi-arid areas into deserts. These are all issues that permaculture design addresses. Our teacher, Geoff Lawton, his family and his team, have done tremendous work in their well documented project ”Greening the Desert”, showing us all the possibility that permaculture holds to regenerate very degraded land. For us here, we are fortunate to live in a fully humid climate, where we get precipitation year round. If we do have a drought it tends to come at the end of the summer, or early fall. However we also have problems with storm water runoff, not here on our land, but definitely in the lower valleys. This problem will increase with the continued 100 year and 1000 year storms we are seeing more and more frequently. It is important that wherever we are, we take responsibility, but also advantage of the rain water which flows off our hard surfaces (roofs, driveways, patios, walkways and so on).

At this point the Water Map comes into play. This map shows us how the water flows through our land. It is essential to understand the area of Water Catchment which is flowing onto the land from up hill, and how much catchment we have on our land, as well as where that catchment ends up leaving our land. The water map shows all this clearly.In our case we are on a hill, so there is no additional catchment entering the land from up hill and the water more or less leaves the land at a spring at the bottom of the hill.

Understanding our regional watersheds can amplify our understanding of how the water flows on and in our land. Water flow changes from the mountain to the valleys and into the deltas. Highly oxygenated water in the hills with very specific species (with less diversity) changes to less oxygenated water with a greater diversity of life and larger species, as a general principle. Rapidly flowing water causes erosion, which will become readily apparent over time. Bare soil invites this erosion, and is the culprit for the yearly loss of topsoil from plowed fields and construction sites. Permaculture design absolutely designs to stop any erosion from taking place on the land. We also design to store water, whether that be in water tanks or in the soil itself and the life upon it. The runoff from hard surfaces can be directed to plant growing systems, animal waterers, and even for our own water needs. Including ponds (or dams as they called elsewhere), allows us to take advantage of the great abundance that aquatic gardens produce.

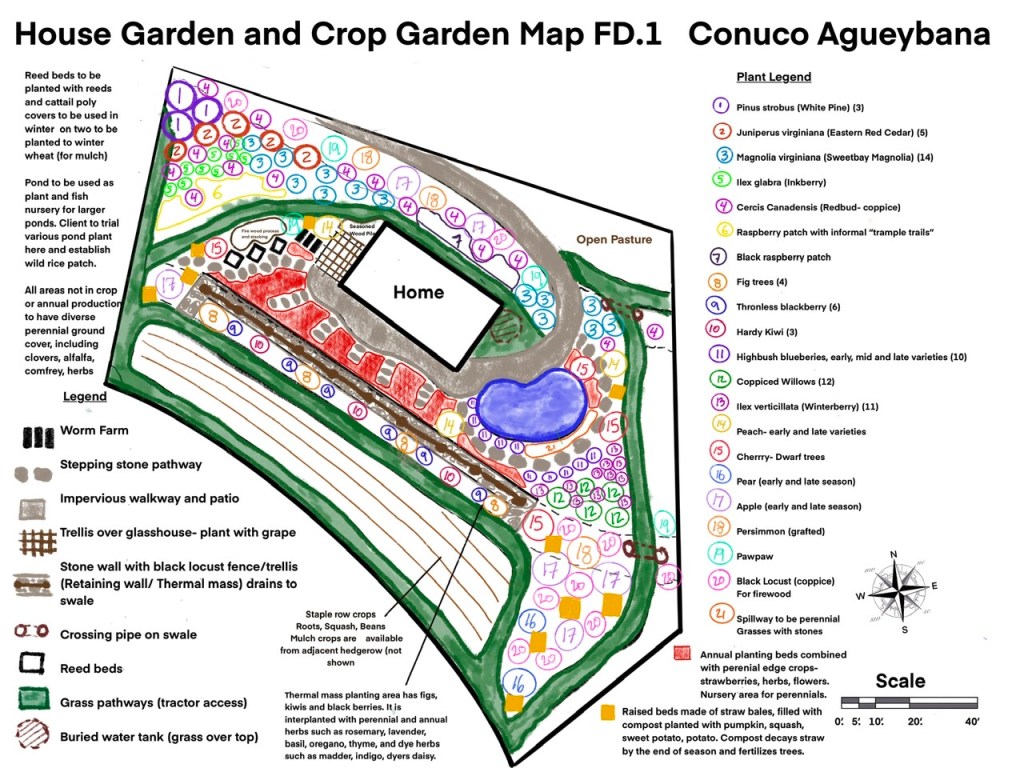

On our land here, we are prioritizing the storing of roof water runoff in tanks for livestock and irrigation, as well as directing rainfall to swales and on to ponds. The ponds will trial important food crops such as wild rice and duck potato, as well as trial decorative pond plants, such as waterlilies, irises, and fish. Rain gardens are yet another technique within the permaculture design tool box, which turn rainwater runoff from an erosive problem into a beautiful and potentially edible solution.

Swales

For those familiar with rain gardens, swales are elongated rain gardens, however with the focus on the plantings in the mound, rather than the bowl. Swales are designed to grow trees, although in smaller gardens they can be used for shrubs and herbaceous plants. Swales catch, spread and soak the rainfall into a plume below the mound, storing the water in the soil rather than allowing it to runoff the surface. The tree roots then form corridors through which rain falling on the mound soaks into the soil. Swales are an excellent way to reforest an area, to create a food forest and to create hedgerows, and we are using them for this purpose here.

Access

Many of us, who struggle with icy shaded hills in winter and washed out gravel driveways after rainstorms, can attest to the fact that badly designed access is one of the most costly mistakes made in the layout of many farms, hamlets and villages. Access often becomes erosion nightmares, consuming large quantities of gravel and requiring hours of regrading. Permaculture design process generally put access on contour wherever possible. By being on contour there is an ease of passage (you are driving or walking on the level) and very little erosion, therefore very little regrading or gravel application that is needed. When this is not possible, putting the access up a ridge-line where the water sheds in both directions off the track is a second option. As a general principle access, if it does go up or down a hill should be as gentle as possible. Carefully thinking through where the access needs to reach as well as what kind of access is required, is an important process. There may also be aesthetic considerations for access, especially when approaching a house. When we are designing for intergenerational benefit, access may be well worth re-routing as our future generations will thank us.

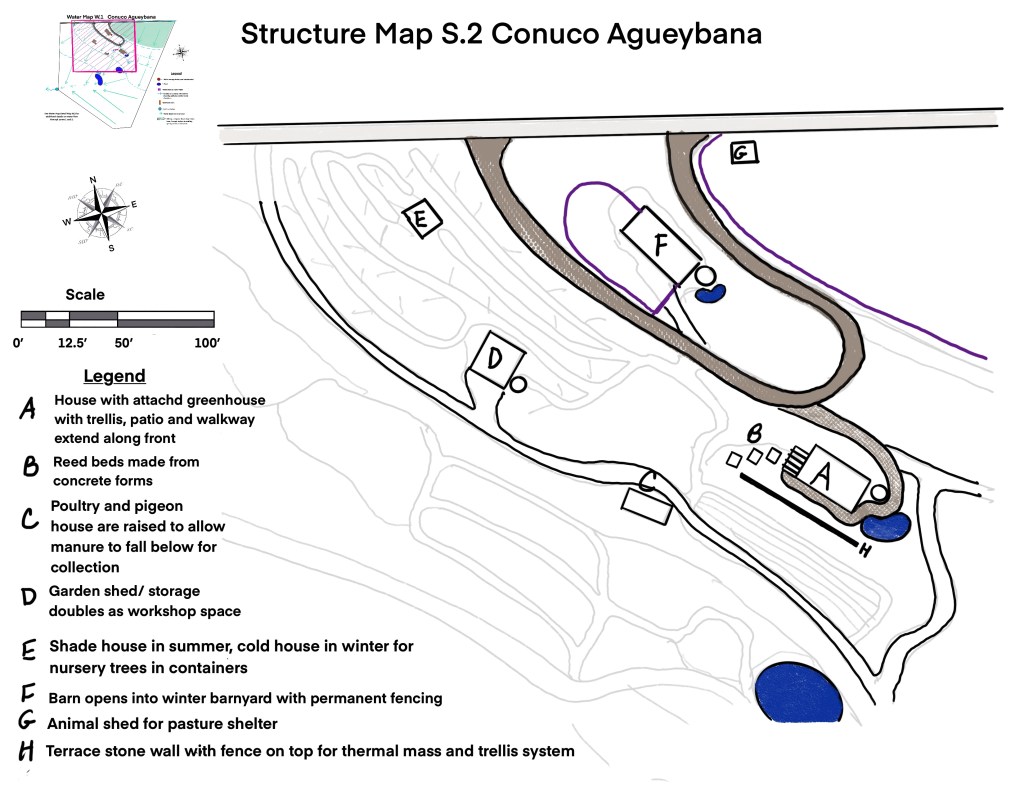

Structures

Finally structures make up the final component of the backbone of the design process. Taking into account winds, sun angles, slope and aspect, existing vegetation, and views, buildings can be located in prime positions to passively heat and cool to a great extent. Placing a house on top of a hill, may afford us excellent views, but cost a small fortune in additional heating costs as well as windswept kitchen gardens drying out far more quickly than their more sheltered cousins. A walk up a hill on a cold winter day will quickly let us know how profound this difference can be. Our animals also benefit from protection from cold and drying winds, especially more delicate ones, such as bees and some birds. As a general principle, leaving the hilltop for forest and siting buildings lower down in the ”sunbelt” of a sunny slope is ideal for our temperate climate. For structures that already exist in less than ideal locations, we can use windbreaks to give them protection, using carefully designed tree plantings to lift the wind up and over the structure.

Permaculture design uses a tremendous amount of common sense. We place structures in a way that creates an ease of movement for people especially as they go through their daily routines. Checking gardens, watering, feeding animals, and creating and turning compost should all happen with efficient movements and flows. If kitchen waste moves from kitchen to chickens or worms, it should be a short journey. If weeds from the garden and cuttings from the food forest go to goats, again this should be a short journey, preferably on contour. Manures from the winter livestock barn should not have to travel far to the composting area and from there to intensive gardens, crops and orchards. All these factors go into the very important decisions of where structures should be built.

Water-Access-structure: The backbone comes alive

At this point we are ready to integrate all three maps to form a Water-Access-Structure map showing how they all interrelate and interact. Rainfall on structures creates opportunity for water storage, ponds and swales. Rainfall on access can feed swales and ponds. Access connects structures, swales, ponds and gardens. If an access crosses a swale, we see that we need a crossing pipe to allow us to cross the swale without disrupting the water flow. Culverts can direct water off access drives to swales to reduce downhill erosion hydrate orchards and hedgerows. In the interplay of these three aspects of our design, more niches are developed than we realize, and they will make themselves known to us as we observe and interact with our land through implementing our design.

By getting the back bone aligned through our design process, we are starting off with a foundation that increases our quality of life, reduces maintenance and harmonizes with the landform, climate and multiple other aspects of the land.

Permaculture “zones”

Prior to jumping in and planting food forests, gardens, building pergolas and fences, a contemplation of zones will inform our design process greatly. Permaculture zones are numbered 0-5, with 0 being the home (or business center if that is what we are designing) and 5 being “wilderness”. Zone size will vary according to our needs and desires. Zones are primarily determined by the frequency with which we visit them. Zone 0 we inhabit most of the time, our home. Zone 1 is generally the most accessible from zone 0 and contains high maintenance and high frequency spaces such as kitchen gardens, seedling nurseries, chick nursery, children’s play area, espalier (or highly pruned) dwarf fruit orchard, herb garden and so on. We will visit zone 1 several times a day. At a further distance zone 2 starts, it contains things like chicken runs, possibly a milking barn for goats, food forests, and main crop gardens with staple crops such as potatoes, onions, roots, squash and so on. It may well contain the winter livestock barn, or a cow milking dairy. We may visit zone 2 once or twice a day. Beyond this the more traditional ”farm zone”, zone 3 begins, containing pastures, large nut tree orchards, and larger animals which require more space such as cows and horses. We may only visit zone 3 once or twice a week. Zone 4 is our traditional forestry zone with timber trees and fuel crops or more wild grazing land for livestock. Zone 4, once it is established may only get a monthly visit. Finally we have zone 5 “the wilderness zone”. While it is rarely true wilderness, it is generally a space where we allow the natural processes of life to unfold without our interference. Zone 5 is a place to go for contemplation and observation of the genius of Mother Earth. What we learn from zone 5 we can apply throughout the other zones. In short while we, as human designers, dominate zone 0, as we travel out through the zones, our human design humbles itself more and more to the natural process of life, and we allow greater and greater degrees of natural design processes to dominate. These zones are by no means concentric circles and are by no means harshly defined zones. They may certainly bleed into each other in the more naturalized design, or they may be sharply defined in a more classic design without losing their value. While we may map out simple zones initially, we may discover zones within zones. For example we may discover that a highly traveled pathway in zone 3 starts to evolve more like a zone 2 garden.

Once zones are established, when bringing in a new element, for example bees, we can think about what zone they should be in. Since bees may require a monthly visit, but not necessarily a daily visit, we may want to put them in zone 3 or 4, however their activities (of pollination) may be needed in zone 2, so perhaps they should go there. The zones provide a guide for us in thinking about where to position different elements. If we are bringing in a chestnut tree that will grow very large, we may not want it in zone 1 where it may shade out our kitchen garden. This way we create harmonic spaces, avoiding the chaos that can erupt when we bring an element into an inappropriate space.

Circling back around- Taking our W.A.S. Backbone and evolving it to our unique style and expression

At this point we have gone through a specific permaculture design process. This process has clearly defined access, structures, and water elements, created zone spaces, and greatly deepened our understanding of our land. We have researched our location, climate, patterns and pulses of both raw and living elements. The design thus far has not yet specified species or placement of plants or animals. A good basic backbone for Water, Access and Structure provides a foundation for any degree of complexity in our living guilds and systems that we may want to work with. This junction is where the vision of the human beings becomes vey important in directing how we are going to evolve our natural living processes on our land. It is also a point at which more standard concepts of landscape design may come into play for aesthetic and flow reasons. Concepts such as: sight lines, form, patterns, space, light, thresholds, frames and more may play major roles, especially in our zone 1 spaces, but could certainly be used in all our zones. As a traditional gardener, the feel of a garden is very important. The beauty of Permaculture Design Principles is that they can be used in conjunction with more traditional landscape design concepts and techniques to develop a range of permaculture garden styles, from very natural gardens that seamlessly blend with the natural vegetation around them, to walled gardens, more formally arranged and symmetric gardens, to more minimalistic contemporary gardens.

The permaculture design process is both an art and a science. While developing the W.A.S. backbone relies perhaps more heavily on science (laws of physics, study of climate, soil, and so on), the expression of plants and animals on top of the backbone is more art than strict science, especially if we are designing a home where non-tangible benefits are perhaps more important than in a business setting that is geared more towards strict production.

Designing the living guilds and systems

Living systems are full of connections between living and nonliving elements, so many, in fact that we can never fully comprehend all of them. Major elements, such as trees and domestic animals can be easily seen, and relationships between trees can be observed. They may enhance each others growth, have no discernible effect, or have some kind of inhibitory effect. Our classic example here of potential inhibitory effect is black walnut and bamboo. Planting nitrogen fixing legume trees such as black locust, would most likely benefit its neighbors. Bringing honey bees into proximity to an orchard will increase pollination of the fruit trees, whereas allowing herbivores such as cows in could very likely destroy the orchard. Many flowers will attract predatory insects who will control garden pests. Ducks will reduce slugs. Chickens can break up weed and pest cycles before planting or between crop cycles. We can start with the larger element relationships that we do understand or can more easily observe and continue to deepen our understanding as we evolve with our design. This is where intergenerational knowledge becomes very important as some of the interactions and patterns we observe are quite long patterns, and may take more than a lifetime to really notice. Certainly when we are looking to evolve mixed timber plantings, we are looking at very long cycles.

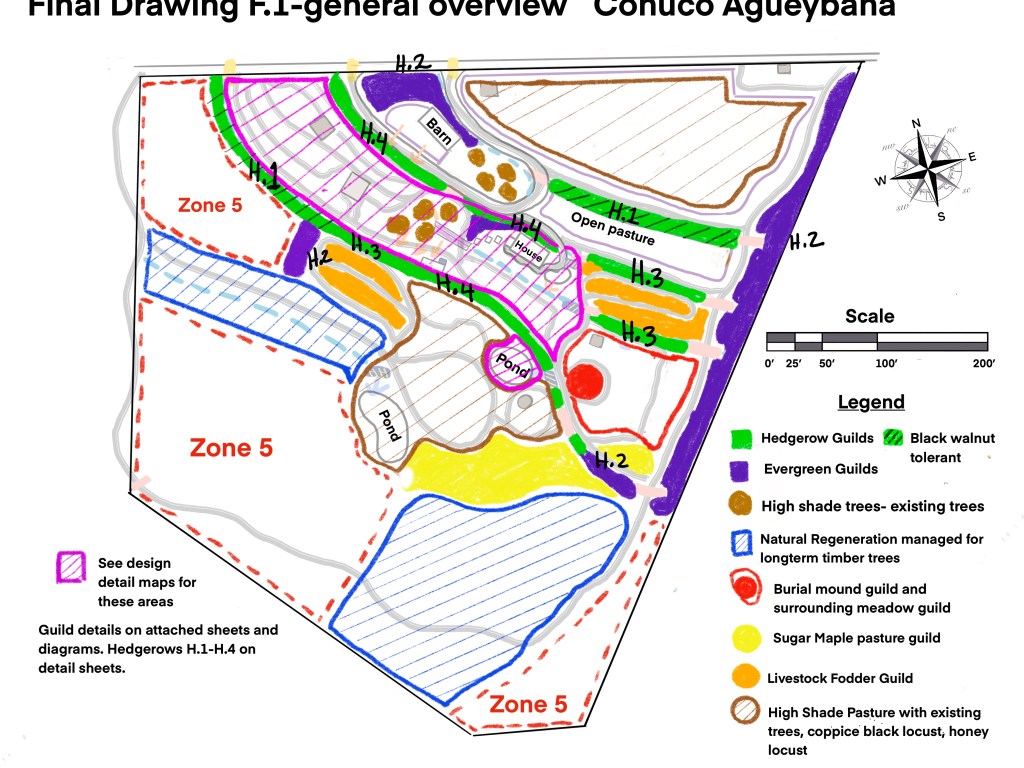

Once we have our zone map, we know where various guilds of living systems could fit within that. For a larger space, we may need multiple maps to elaborate on all the plantings. The zone map can progress into a map which, in broad strokes, outlines what type of guilds we will be placing in various spaces. The map below designates hedgerows, a major guild in our climate and for our purposes, as well as timber areas, and other major guild type areas. In our area, black walnuts are a natural regeneration tree. There are areas we have decided to exclude them, because they will inhibit many common food crops as well as some trees. In other areas they are allowed to grow along with other species, and in some spaces they are already the dominant tree species. They have the effect of reducing the diversity of plants around them. Knowing this, they are a major element to be aware of in our design here.

Hedgerows on swales

Hedgerows were the fence lines prior to modern fencing. Not only did they keep herbivores contained or excluded, they also provided fodder, fuel wood, building materials, and an array of herbs, fruits and berries. In our design here we have chosen to primarily plant hedgerows on our swales. Because they receive a great deal of sunlight, plus the additional irrigation from the swale, these have the potential to be very abundant systems. Edges such as hedgerows, forest edges, river edges and so on are very important within a permaculture design as they are the spaces of maximum abundance and maximum biodiversity.

From this starting point, various iterations are developed such as ones geared to allow black walnuts, ones which will be more highly maintained with more plants of high value to humans, or ones which will primarily be geared towards providing fodder for sheep and goats. Regardless of our intention for the hedgerow in terms of what it will produce for us, it will greatly increase habitat for untold numbers of birds, insects and other animals. The soil created by the hedgerow will also house an increasing abundance of soil life increasing the health of the ecosystem overall.

Food Forest

A food forest is a diversified, designed, forest modeled on a forest edge ecotone, where we plant useful species (food, medicine, materials) and their support species. There is a whole process that is undertaken in the growing of the food forest and it will dramatically change in aesthetics and products as it develops. As it is modeled after a forest edge, it contains various layers from herbaceous and root crops to shrubs, small and tall trees and the vines that climb up them. Food forests can be designed and maintained as relatively simple systems for more mechanized productive purposes, or evolved as highly complex systems full of new relationships and new species forming, appearing or being introduced over time.

Zone 1 garden or kitchen garden

In a more urban or suburban setting the zone 1 garden will take up most of the space. This is your classic kitchen garden, intensively planted and maintained with a very high level of biodiversity. It can contain human centric spaces such as patios, pools, outdoor kitchens, and other recreational areas. Trees in this space will usually be smaller, pruned more and espaliered. Thermal masses such as stone walls, boulders and ponds can be used intentionally to create warmer niches, including adding to the warmth of the house. Garden bed shapes can maximize edges and niches. This is where your typical annual vegetables will appear and most time will be spent. Zone 1 gardens can vary from the more information naturalized one designed below to ones grown in city courtyards.

Water features-ponds

Water features are a very popular aesthetic in many gardens. Within permaculture design we look at what species can be grown in and around ponds or streams that could provide some of our needs, be that a food such as duck potato or lotus root or fish, or a nursery product such as waterlilies. Around our ponds, a diversity of plants will thrive which would struggle elsewhere. Additional benefits such as frogs and dragon flies, and recreation can also be major aspects of our ponds. Unlike your typical aesthetic water feature in a conventional design, permaculture design uses ponds to absorb rainwater runoff, therefore spillways are carefully calculated and positioned so as to not create problems with erosion. As long as the pond has fish, there will be no mosquitos produced. Having a balance between the fish and plants is very important for maintaining pond health. A variation on a pond, a natural swimming pool, is increasing dramatically in popularity today as people turn away from swimming in heavily chlorinated pools to designing biological processes to clean the water naturally.

Special uses

The vision for a land, can often include special uses, such as space for education, extended space for children’s learning and playing, areas for various crafts, spaces design to attract certain wildlife, special trails, and so on. These can be in a variety of zones from a children’s play area in zone 1 to walking trails with educational signage in zone 5. Often aesthetics and space play key roles in their design. The feeling evoked as one enters the space can play a key role in the design process. Cemeteries are just one of these special use spaces that can require an intense design process. There is a growing interest in natural burials, and more biodiverse, holistically maintained cemeteries. The permaculture design process can greatly support the evolution of a natural cemetery or burial space as we are doing here. The burial space here will be a combination of naturalized meadowland and shrub land with predominantly native plants with high value to wildlife, especially birds, butterflies, bees and insects.

In conclusion

A permaculture design process is a constantly evolving journey of working with the landform, climate, animal and plant life, soil life, and our own visions for the land to manifest a garden, a food forest, a farm, a timberland, a meadow, a home, or any number of combination of those things and more. In this process we bring physical laws (water, gravity, thermodynamics, weather cycles and phenomenon) together with complex biological life and the web of interrelationships the various forms of life may have with each other (much of which is beyond our understanding or perception) to move away from monocultures and simplistic landscapes which require massive chemical and/ or labor inputs.